By Srinidhi Murthy

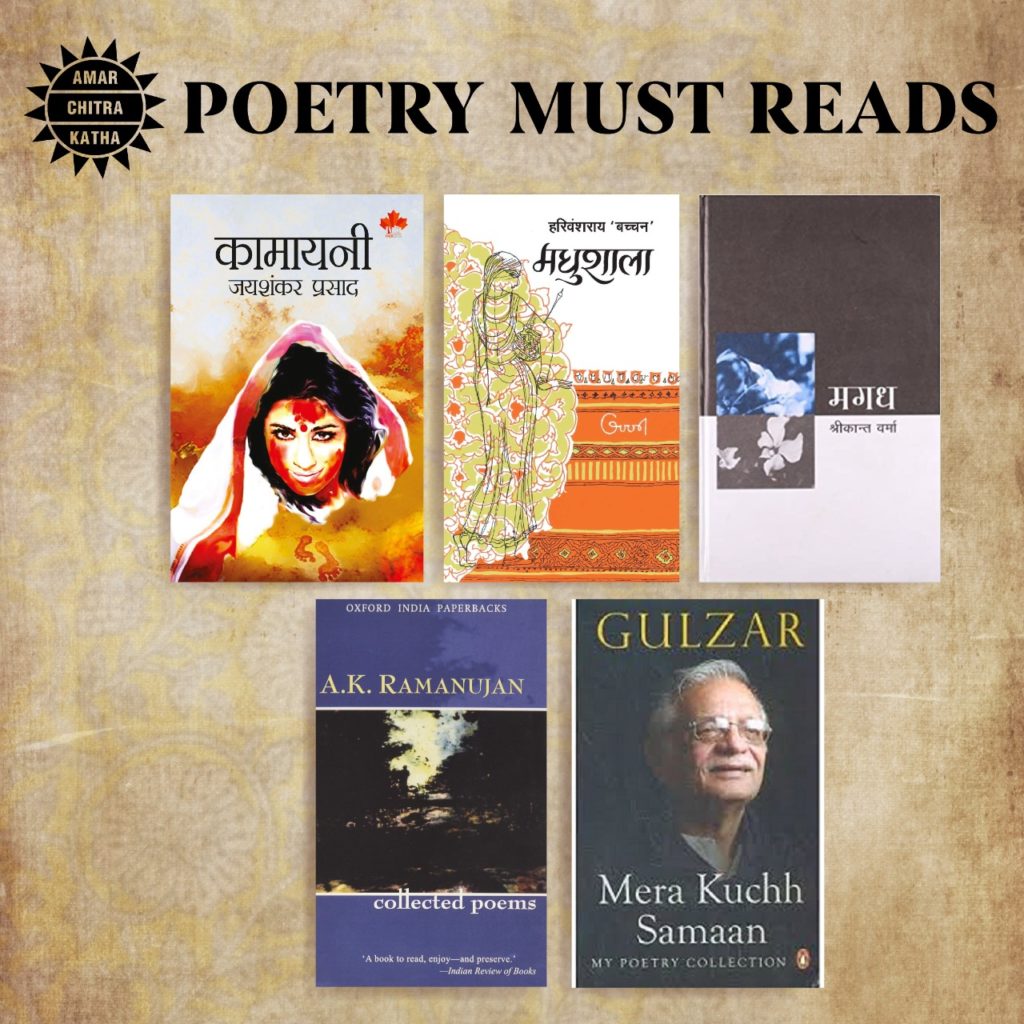

Rabindranath Tagore is considered one of the pioneers of the Bengal Renaissance, which took place during the 19th century. He has given Indian literature numerous unforgettable characters, a lot of whom were women. Tagore’s heroines were complex and fierce while also being flawed and vulnerable. They fought for equal status in society and refused to bow down to the expectations of society in a way that was rare for the time. Read on to learn more about some of Tagore’s most compelling heroines.

Mrinal from Strir Patra (A Wife’s Letter)

Set in the late 19th century, Strir Patra is the story of Mrinal, a woman married into a zamindar household. Mrinal is depicted as an intelligent and observant woman who feels stuck in mundane, domestic life after marriage. Her intelligence is seen as a disadvantage and her beauty seems to be the only thing society values. As the story progresses, she is introduced to Bindu, the widowed cousin of Mrinal’s sister-in-law. Bindu’s plight makes Mrinal even more aware of the patriarchal and oppressive nature of her in-laws. After Bindu commits suicide, Mrinal becomes completely disillusioned with the idea of family and marriage. In her letter to her husband, she explains her decision to leave him, in order to finally find her freedom.

Kalyani from Aparichita (The Unknown Woman)

Kalyani is the protagonist of Tagore’s story, Aparichita. In the tale, Kalyani is set to marry Anupam, but her father breaks off the match on the wedding day due to demands of dowry from the groom’s uncle. After a few years, a guilt-ridden Anupam proposes marriage to Kalyani again. However, the independent protagonist rejects his proposal and tells him about the new direction her life has taken. Instead of letting her cancelled marriage be an impediment, Kalyani ventures into the world to find her purpose and identity. She dedicates her life to educating underprivileged women and helping them lead a life of dignity. Through Kalyani, Tagore shows a woman choosing to find meaning outside of marriage without letting patriarchal traditions dictate her significance in society.

Giribala from Maanbhanjan (Fury Appeased)

Giribala, the protagonist of Maanbhanjan, is married to a wealthy zamindar. However, unknown to her, her husband falls in love with a theatre actress and plans to leave Giribala for her. While spying on her husband, Giribala is introduced to the world of theatre and finds herself fascinated with the art. After her husband leaves her, the heroine decides to emerge stronger than before. She reinvents herself and pursues a successful career as a theatre actress. Through Giribala’s story, Tagore highlights how women can find success in their chosen fields too. The protagonist is special since she does not choose to become an actress to regain the love of her husband. Rather, she does so for her own love for theatre.

Mrinmoyee from Samapti (The Conclusion)

In Sampati, the protagonist is a young, fun-loving woman, Mrinmoyee, who enjoys her freedom. However, everything changes for her when she is married off to a wealthy and educated gentleman, who falls in love with her strong, unique personality. However, on the day of the wedding, Mrinmoyee questions her husband. She confronts him about her lack of choice in the decision to get married and thus refuses to reciprocate his feelings. Over the course of the story, she slowly begins to accept her husband and return his affection, but by her own choice, taking her own time. Through Mrinmoyee’s story, Tagore alludes to women being made voiceless and not having any say even in their own life choices.

Kamala from Musalmanir Golpo (The Story of a Muslim Girl)

In a short story set in the 19th century, Tagore introduces us to Kamala, an orphaned girl raised by her uncle and aunt, who resent her as a burden. Soon, Kamala’s marriage is arranged with the son of a wealthy man. However, their wedding procession is attacked by robbers. To her surprise, her fiancé and other relatives all flee, leaving her at the mercy of the attackers. She is rescued by Habir Khan, a respected Muslim gentleman, who takes Kamala to her house. When her aunt and uncle refuse to take her back, Kamala ends up staying with Habir Khan. She finds a better life, full of respect, at her new home, where she has the freedom to practice her own religion and make choices for herself. When the robbers attack Kamala’s cousin Sarala, she is no longer afraid. She saves her cousin with help from Habir Khan, and delivers her safely to her house. Through the story, we see the evolution of Kamala and the effect freedom and respect has on her personality.