By Jayshree Misra Tripathi

The Bhaumakara Reign

In the first half of 8th century CE, the Bhaumakara dynasty had conquered and unified the kingdoms of Kangoda, Kalinga and Toshali, in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. Their rule would extend for over two centuries, from 736 CE to 945 CE. This period was also a time of tremendous change in society, as Buddhism and Jainism evolved during their early rule, and later, Hinduism was revived.

During their reign, the Bhaumakaras established trade and cultural links with South-East Asia. Their maritime trade is evident from inscriptions of the period as they include the words ‘samudrakara bandha’ which translates to ‘ocean tax’. Due to these links, the region experienced overall prosperity. It was the golden era of Utkala or the Land of Exquisite Arts.

The Widow Queens

It was during this period that the Bhaumakara Queens, who were widows, reigned for almost 200 years but, initially, not in direct succession. Nowhere else in the land had widows ascended the throne. Earlier, royal women could donate land and order temples to be built but could not participate in the administration of the kingdom.

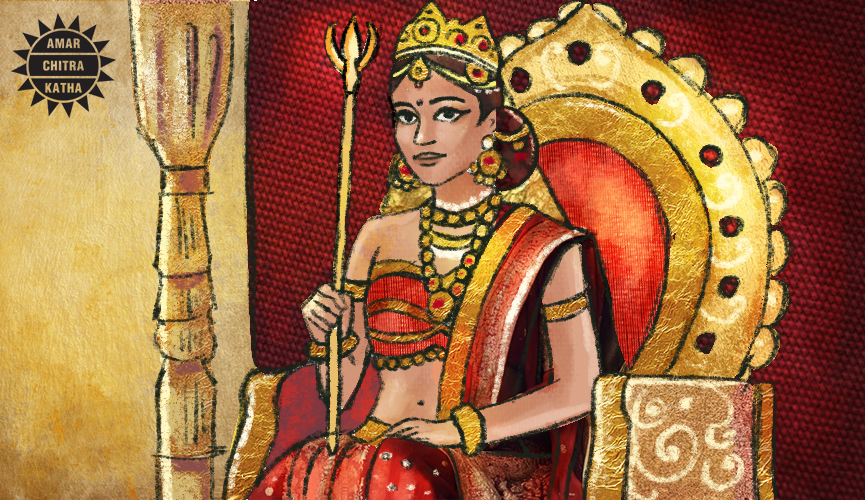

Tribhuvana Mahadevi – the First Queen

The first and most acclaimed of the widow queens was Tribhuvana Mahadevi, who ascended the throne in 845 CE, after the death of her son. The charters of Dhenkanal and Talcher state that Tribhuvana Mahadevi restored peace in her kingdom, overcoming rebellions with the help of her father. She appointed honest officials to oversee her subjects, administered a light-tax and used the royal treasury to build temples, monasteries and charitable shelters for the poor.

Tribhuvana Mahadevi commanded an army of men and women, estimated to have a strength of 3,00,000 people. These figures are inscribed on copper plates discovered in recent archaeological excavations. Royal women were skillful warriors, having learnt the art from their childhoods. Women were respected in the kingdom. In fact, early Vedic marriage hymns hoped that young brides would speak with composure at assemblies held for the welfare of the people. There is no evidence of Sati or Purdah in palm leaf inscriptions or copper-plate charters. Women in her kingdom were educated and permitted to study the sacred texts and conduct sacrifices. They even wore sacred threads, like the menfolk. Royal women were granted administrative rights to issue charters and land grants.

Her charters state that she truly cared for her people and built roads, wells and bridges. She performed rituals in temples and donated ghee, milk, curd, betel-leaf, sandalwood paste and incense. She participated in discourses on religious doctrines. Tribhuvana Mahadevi gave from her personal resources to fight wars, stave off pestilence and famine. Harmony prevailed during her rule.

Subsequent Queens

Tribhuvana Mahadevi abdicated her throne after eighteen years of rule, to her grandson, Santikara Deva II, when she felt he was ready to rule. Fifty years later, another widow, Prithivi Mahadevi, ascended the throne, after the mysterious death of the reigning king, her brother-in-law. She assumed the title of Tribhuvana Devi the Second. However, as she was suspected of having her brother-in-law killed with the help of her father, she was not accepted on the throne by the court and was deposed, after a few years of rule. Her name was not included in their genealogical tree.

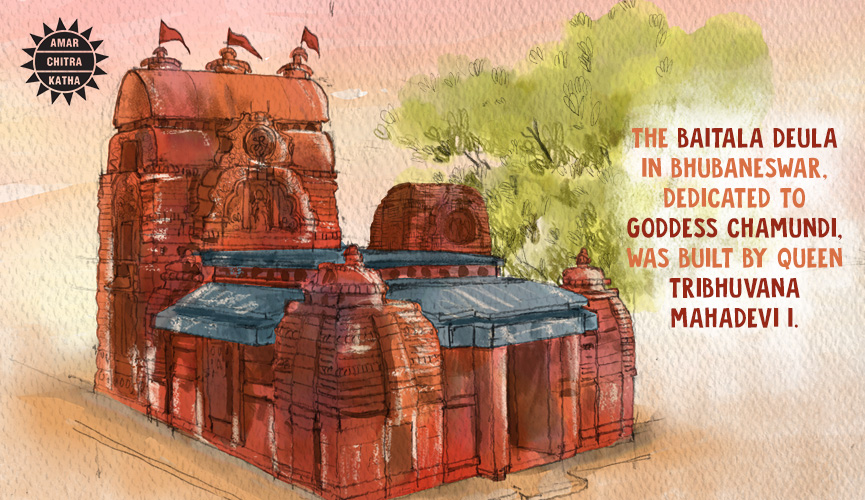

The last male ruler of the Bhaumakaras, Subhakara V, was succeeded by his widow, Gauri Mahadevi, who ruled briefly. She decreed the construction of the Gauri Temple at Bhubaneswar. Her daughter, Dandi Mahadevi, was a powerful ruler and administrator. However, she died a premature and mysterious death. She was succeeded by her stepmother, Vakula Mahadevi, a princess of the Bhanja dynasty. Little is known of her rule.

After her, the widow of Santikara III, Dharma Mahadevi, ascended the throne. She was also a princess of the Bhanja dynasty and was the last Bhaumakara ruler. After her death, the kingdom was occupied by the Somavamsi King Dharmaratha.

Sadly, there are few statues or images of these brave widow queens, and only remnants of the monuments they had ordered to be built. Many have been destroyed by later conquerors of different faiths. Intrigue, strife, murder and mystery are deeply embedded in the history of these courageous and inspirational queens of Odisha.

Read about more such inspirational queens only on the ACK Comics app!