By Shree Sauparnika V

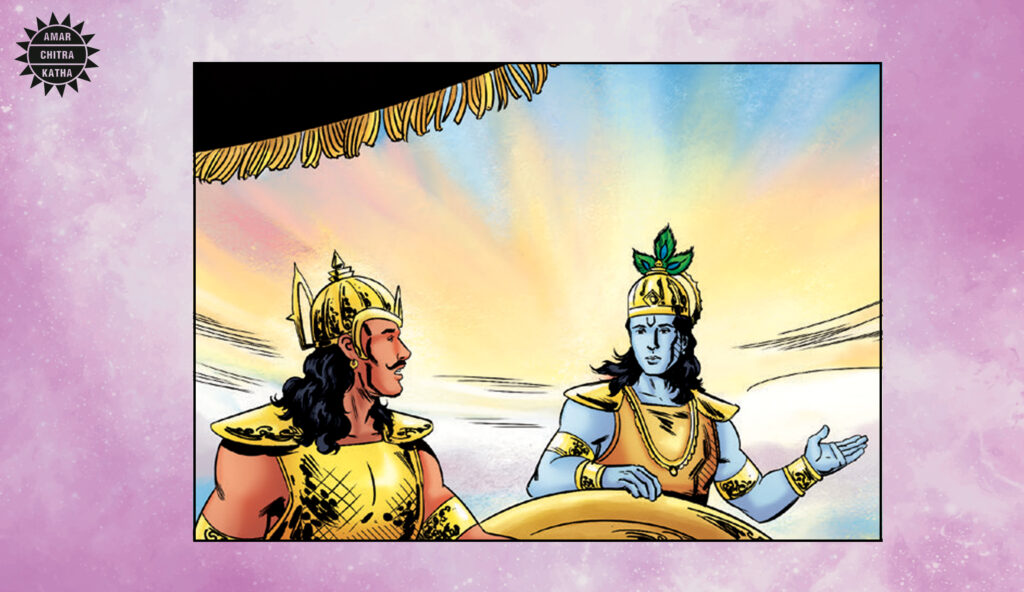

Every year, Guruvayur Ekadashi — also observed as Gita Jayanti — reminds us of the power of reflection and conversation. This is the day when the Bhagavad Gita, born from Krishna’s dialogue with Arjuna, was first spoken. It is a moment that celebrates both faith and the timeless importance of conversation, reminding us that some of the deepest truths in our traditions emerged not from commands, but from dialogue.

Across civilizations and centuries, dialogue has been one of humanity’s most enduring ways to explore difficult questions. A dialogue is dynamic: full of questioning, resistance, and discovery. Truth often emerges not from a single voice, but from the space between two or more.

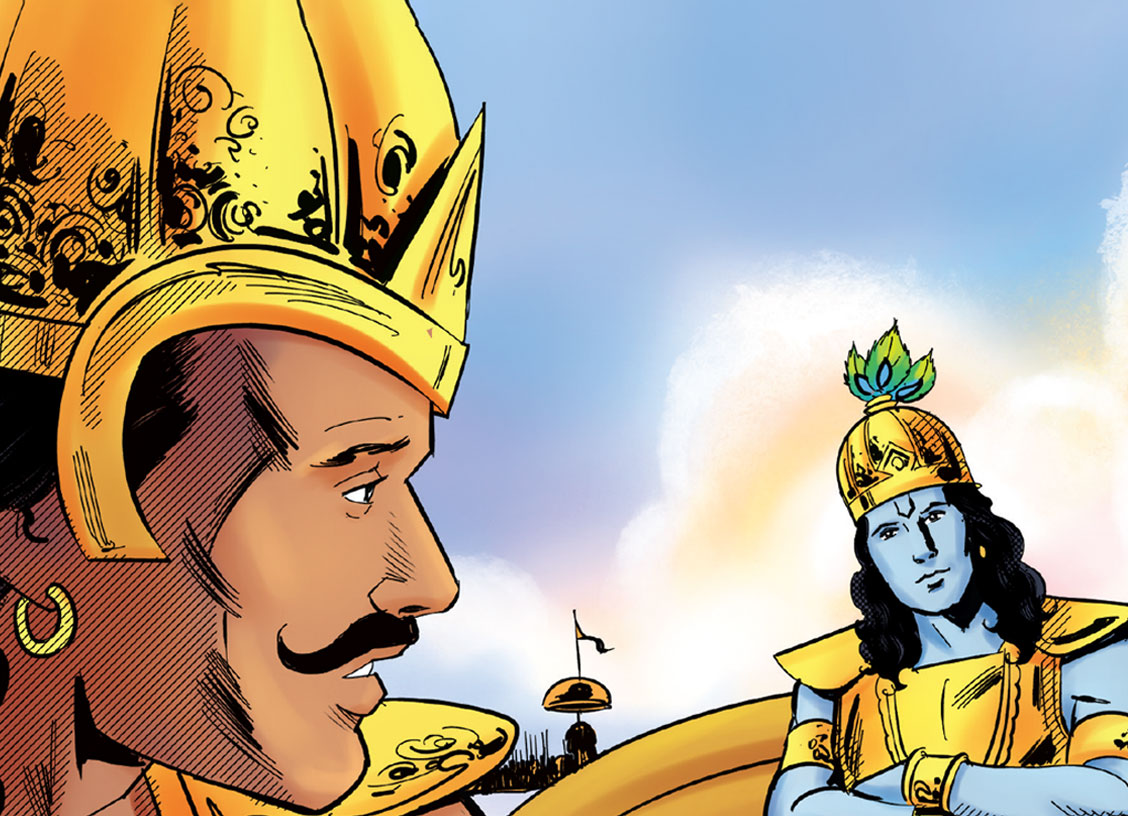

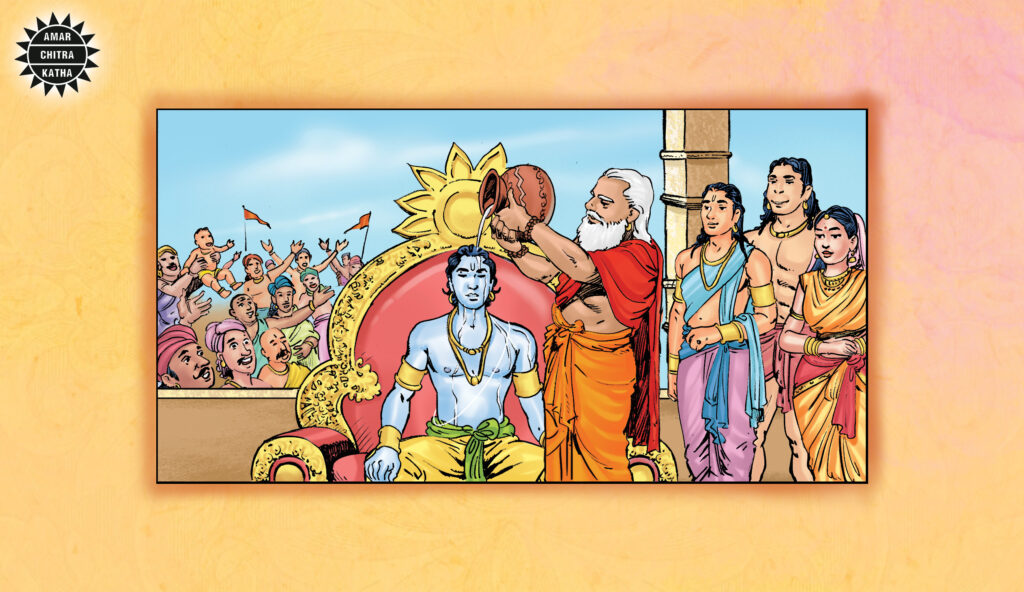

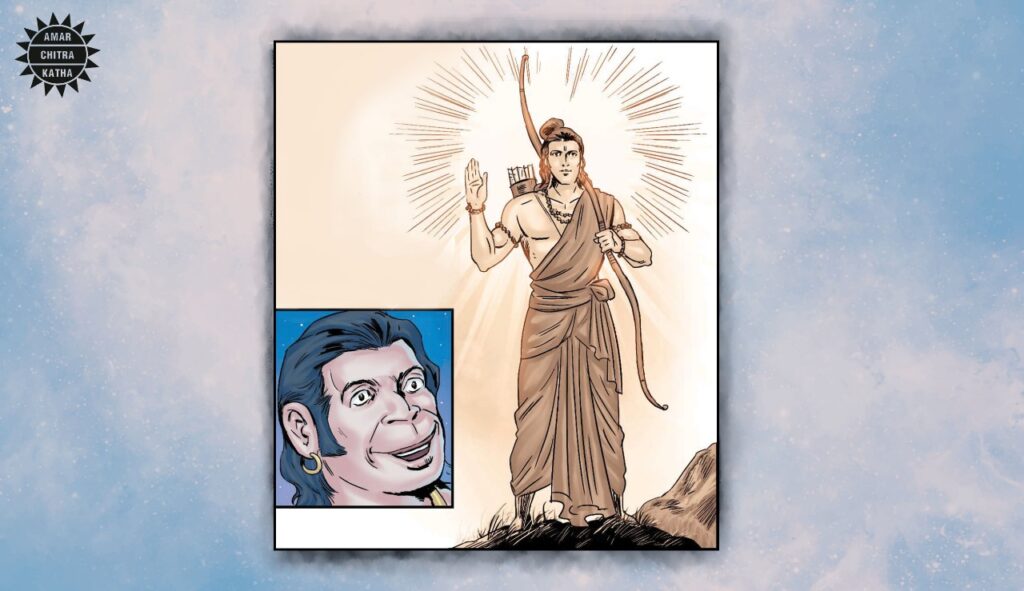

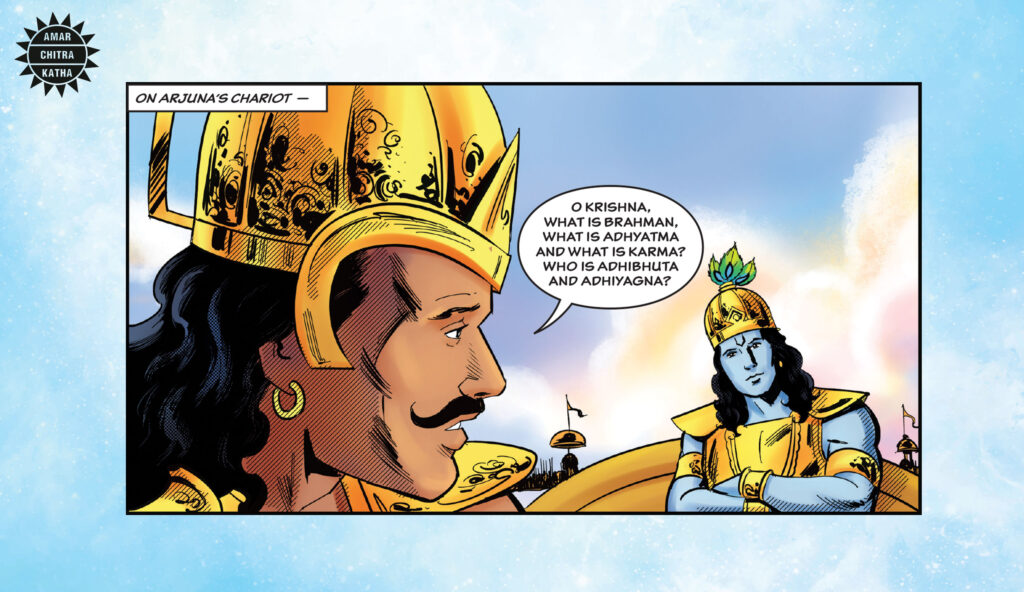

In India, this tradition runs deep. The Upanishads unfold through debate and inquiry, where teachers and students explore complex ideas together. The Mahabharata carries this spirit forward. It is framed through multiple storytellers and listeners, each adding a new layer of meaning. The sage Vyasa is said to have dictated the Mahabharata to Ganesha. Within it, Sanjaya narrates the Kurukshetra war to Dhritarashtra, answering his questions about the fate of his sons. And before the battle begins, another powerful dialogue rises — the Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna reveals to Arjuna the nature of duty, action, and liberation.

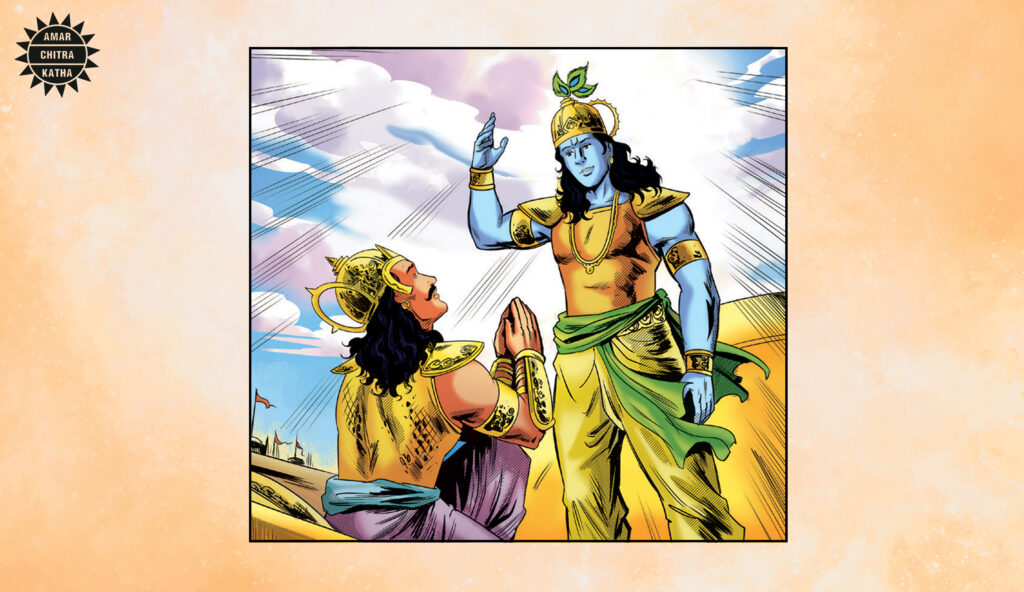

It is striking that ideas like dharma, karma, and moksha were not delivered as sermons but through conversation. The layered structure of the Gita helps us understand its depth and complexity. Arjuna’s doubts strengthen Krishna’s responses. His fear and confusion make the text relatable and human. Without Arjuna’s voice, Krishna’s teachings might have felt distant; with it, the Gita becomes universal. Each reader can find their own questions echoed in Arjuna’s.

This method was not unique to India. In ancient Greece, Socrates also taught through dialogue. He walked the streets of Athens asking questions about everything from governance to the inner soul. Instead of lecturing, he probed until clarity emerged. Today, this approach is known as the Socratic method, the foundation of philosophical inquiry and legal education. Interestingly, Socrates wrote nothing himself — his ideas survived because others recorded his conversations.

Dialogue shaped Buddhism too. Many Buddhist sutras present disciples asking questions, with the Buddha responding patiently, and turning abstract truths into human conversation.

Dialogue sits at the heart of our institutions. Parliaments debate to test ideas in the presence of opposing voices. India’s ‘Question Hour’ demands that ministers explain themselves publicly. Courts function through argument and counter-argument — lawyers speak, judges question, and truth is pursued through exchange, not assertion.

So how does dialogue differ from storytelling? A story is linear and moves forward along a predetermined path. Dialogue is recursive — it circles back, revises, clarifies, and transforms. In the Bhagavad Gita, when Arjuna asks, and Krishna replies, the exchange is not just a transfer of knowledge. It is a transformation, one that reshapes both teacher and student, listener and reader.

But do we still practice true dialogue today? Dialogue requires humility, patience, and listening. It asks us to hold silence long enough to hear another voice. Without this, even the most sacred traditions lose their power. With Arjuna’s honesty, Krishna’s patience, and Socrates’ curiosity — we can soften divisions and find clarity again.

The art of dialogue is ancient, human, and still within reach. All we have to do is ask…and listen.

Read more stories on mythology and history on our ACK Comics App.