by Shree Sauparnika V

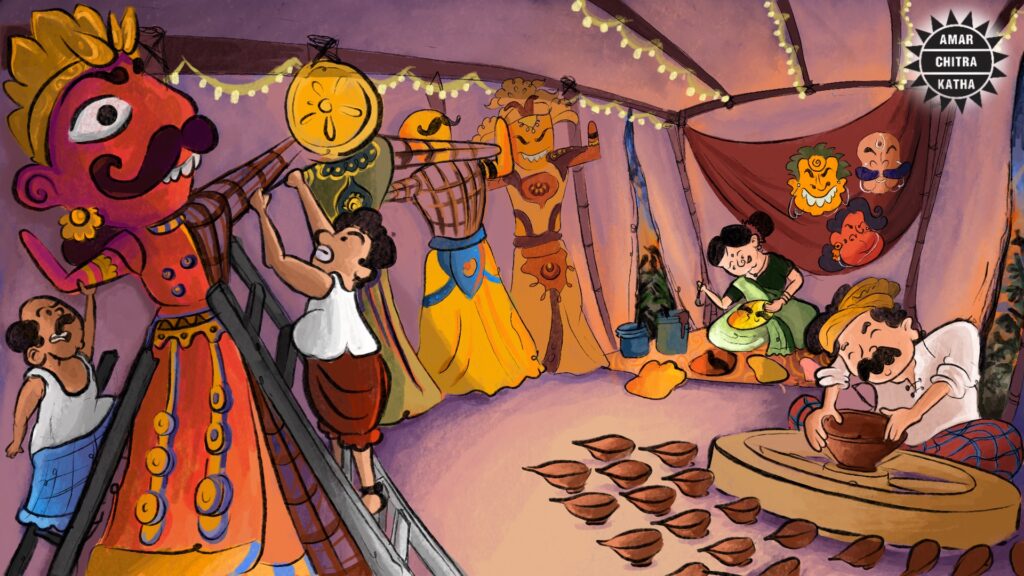

Makar Sankranti marks a special moment in the Hindu calendar: the day Surya, the Sun God, begins his northward journey, known as Uttarayan. This celestial shift is deeply significant, symbolising the return of light, warmth, and hope. As the days lengthen, the harvest is gathered, and life moves toward renewal, making it an auspicious time celebrated across India with prayers, feasts, and festivals.

In many parts of the country, particularly in western India, this reverence for the sun is celebrated in the sky itself. As Surya rises on Sankranti morning, rooftops fill with people, paper kites, and reels of string. Flying a kite becomes a vibrant way of greeting the Sun God—sending colour, joy, and gratitude upward. This beloved tradition has a long and layered history that spans centuries, regions, and cultures.

A Journey from the East

While the absolute origins of the kite are debated, most historical accounts credit China as the place where the kite first took shape. The earliest written reference dates back to 206 BCE, describing military uses—such as a kite flown to intimidate the army of Liu Pang, and later, General Han Hsing using one to calculate the distance for tunnelling beneath city walls for a siege in 169 BCE.

As trade and cultural contact increased along routes like the Silk Route, kites travelled across regions, much like silk, paper, and ideas. They are believed to have reached the Indian subcontinent from the East, brought by Buddhist missionaries. From India, the practice is thought to have spread further west, reaching Arabia and Europe.

Kites take root in India

Within the subcontinent, kites (variously called gudi, vavadi, chagg, or patang) became deeply woven into cultural expression. They appeared not only during festivals but also in poetry, music, and storytelling.

- In devotional poetry: The 13th century Marathi poet-saint, Namdev, mentioned gudi (kites made from kaagad or paper) in his gathas. 16th century poets Dasopant and Ekanath also wrote about kites, referring to them as vavadi.

- In epic stories: The 17th century poet, Tulsidas, in his Ramcharitmanas, tells a playful tale of Rama’s kite (which he calls a chagg) flying all the way to Indralok, only to be retrieved by Hanuman. References to kites are also believed to be found in ancient texts like the Ramayana and the Vedas.

Under the Mughals

During the Mughal period, kite flying developed into a popular sport, particularly among the nobility. Designs were refined to improve balance and aerodynamics, and Mughal miniatures show both men and women flying kites from terraces.

This period cemented the kite’s place in public celebration. A historic event—Emperor Jahangir returning to Delhi after exile—was celebrated by filling the sky with kites; an event remembered today as Phool Waalon ki Sair. In the 18th century, the word patang came to describe the finest fighting kites, replacing earlier names.

A Symbol of Freedom

Beyond religious celebration and royal sport, the kite found its purpose in the spirit of Indian nationalism. During the struggle for independence, patriots cleverly used kites as airborne messengers of resistance. Kites were flown high over cities, bearing messages and slogans like “Simon, Go Back” (in reference to the Simon Commission of 1927). A simple piece of paper soaring freely became a powerful visual symbol of the nation’s own longing for sovereignty. This legacy is one reason why kite flying remains a strong tradition on Independence Day (August 15th), especially in parts of Old Delhi, embodying the joy of liberation and national freedom.

A Living Tradition

Kite flying remains a vibrant seasonal activity, closely linked to festivals like Makar Sankranti/Uttarayan, and in Punjab, to Basant Panchami and Baisakhi.

Today, in western India, especially Gujarat, the tradition thrives. During the kite season, the celebratory cry of “Kai po che!” (I have cut the kite!) echoes across the rooftops. Gujarat celebrates this culture on a global scale through the International Kite Festival, launched in 1989. The state is also home to the Patang Kite Museum, which preserves rare historical kites and paintings.

From its humble origins as a Chinese military tool and its starring role in the courts of the Mughals, the kite has flown across borders and ages to settle in the heart of Indian tradition. On Makar Sankranti, when these handcrafted wings take flight across the subcontinent, they become a timeless symbol: carrying the hope of the new harvest, the joy of the sun’s return, and the enduring wonder of India’s cultural sky.

For more stories on Mythology, History and Folktale, check out our very own ACK Comics App.