Myths Behind India’s Harvest Festivals

- January 13, 2026

Myths Behind India’s Harvest Festivals

- January 13, 2026

by Keya Gupta

The end of winter is when winter crops such as sugarcane, wheat, and sesame are harvested across the country. The harvest of these crops is traditionally celebrated across the country, as Makar Sankranti in many North and South Indian states, Pongal in Tamil Nadu, Magh Bihu in Assam, and Lohri in Punjab and neighbouring regions. Each celebration is shaped by its own landscape, language, and local customs and has its own name and traditions, but the spirit remains the same, of celebrating this period of abundance and renewal.

Another common thread that links all these festivals together is Uttarayan, the period when the sun begins its northward movement in the sky, marking the transition from winter to longer, warmer days. In many traditions, this shift is seen as an auspicious turning point, associated with new beginnings, which is why the bonfires, offerings, and prayers across these festivals are often dedicated to the sun and the forces of nature that sustain life.

To receive more such stories in your Inbox & WhatsApp, Please share your Email and Mobile number.

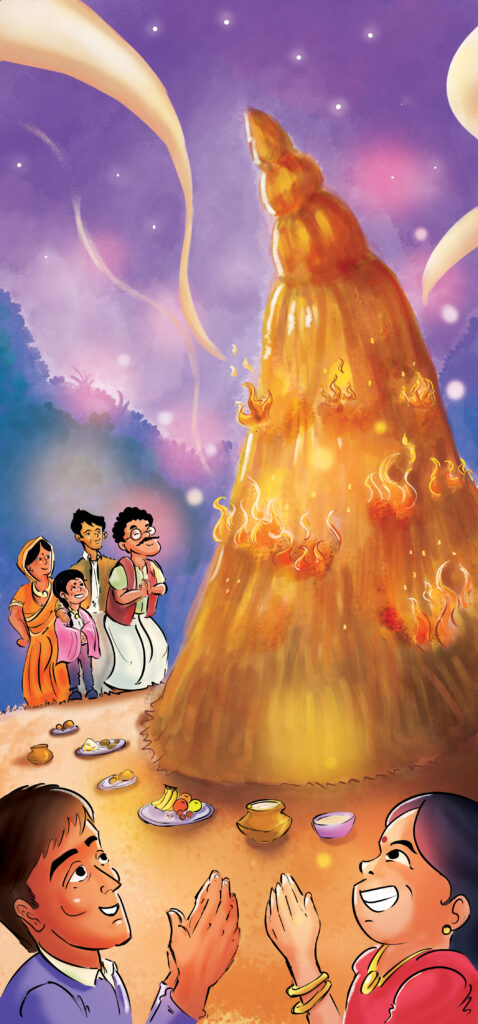

Assam marks the end of the rice harvest with Magh Bihu, which is also known as Bhogali Bihu. Communities gather to construct ceremonial thatched huts called ‘Bhelaghars’ and huge, towering bonfires called ‘Meji’ made from the harvested hay. On ‘Uruka’, the evening before Magh Bihu, the festivities begin, culminating in the burning of the Meji fires at dawn.

For many communities in Assam, the Meji fire symbolises Bheeshma’s funeral pyre in the Mahabharata. Bheeshma was defeated in the war but lay waiting for his death 58 days until Uttarayan believing it to be a time of liberation and renewal. The Meji is symbolic to of Bheeshma’s funeral pyre, a fire that marks his sacred time of passing, tying the harvest ritual to collective Indian mythology.

In Tamil Nadu, harvest is celebrated as the four-day long Pongal, centred around giving thanks to the forces of nature, with freshly harvested rice taking prominence. Each of the four days has its own rituals, focusing on a different aspect of agriculture. On the main day, families make payasam with rice, milk and jaggery, sharing the auspicious food with friends, family and neighbours.

One Pongal legend is about Shiva asking Nandi to go to Earth and instruct humans to eat once a month and bathe daily, but Nandi instead tells them to eat daily and bathe once a month. This angers Shiva and prompts him to send Nandi down to Earth permanently, to help humans plough their fields and grow more food, since they now had to eat every day. Another story connects Pongal to Indra, who was angered that Krishna had convinced the residents of Gokul to worship the Govardhan hill instead of him. Indra unleashed torrential rains until Krishna lifted the mountain on his little finger to shelter the villagers, after which Indra’s pride was humbled, and the festival became a reminder to honour both the sustaining hill and the life-giving rains.

In Punjab, Lohri is celebrated at the centre of a courtyard or village square, around which people circle while singing, dancing, and tossing offerings to the flames. The festival coincides with the onset of warmer, longer days and the harvesting of rabi crops like wheat and sugarcane, so the fire becomes both a source of warmth and a way of thanking the forces that nurtured the fields.

Lohri is also closely associated with the legend of Dulla Bhatti, a folk hero from Punjab. He is believed to have lived during the time of Akbar’s reign and is known as the ‘Robin Hood of Punjab’. He is recounted in folk songs as a rebel who stood up to imperial power and protected the vulnerable. Legends describe him rescuing young girls from being sold, arranging their marriages with dignity, and redistributing wealth to the poor, which is why people still sing his praises around the Lohri fire.

Another legend of Lohri is that of Surajmal, a hardworking farmer who was deeply in love with a girl named Lohri. His village was struck by an especially hard winter and to save his village, he made a vow to Surya, the Sun god, to forgo all personal happiness, even his love for Lohri, if it meant that prosperity and warmth would return to his village. Impressed by this, Surya warmed the earth and crops grew back. In gratitude, people lit fires, offered the first harvest to the flames, and gathered to sing of Surajmal’s faith and perseverance, a memory that, in some traditions, becomes folded into the stories sung around the Lohri bonfire.

Taken together, these festivals show how the turning of the seasons is never just a change in weather, but a moment to pause, remember, and give thanks. Whether in the Meji fires of Assam, the brimming Pongal pots of Tamil Nadu, or the Lohri bonfires of Punjab, the harvest becomes a way of honouring the stories and deities that watch over the land, and of stepping into Uttarayan with hope, warmth, and renewed faith.

Read stories on Mythology, History and Folktales, check out our very own ACK Comics App.

To receive more such stories in your Inbox & WhatsApp, Please share your Email and Mobile number.

Comic of The Month

Shiva Parvati

A powerful demon threatens the gods in their heaven. They need a savior, who, Lord Brahma decrees, will be the son born to Shiva and Parvati. But Shiva, a badly-dressed, untidy, solitary ascetic, seems to enjoy bachelorhood. Even Parvati's unmatched beauty aided by Kama, the god of love, seems unequal to the task of enchanting the stern lord. This illustrated classic is based on Kumara Sambhava of Kalidasa.