Popular Board Games of Ancient India

- December 17, 2021

Popular Board Games of Ancient India

- December 17, 2021

By Kayva Gokhale

Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic forced the entire world inside their homes, indoor games have become a more popular method of passing time. While families everywhere indulge in games of charades and cards, let’s take a look at some little-known ancient Indian games that were the predecessors of board games like Ludo, Snakes and Ladders, Chess and more.

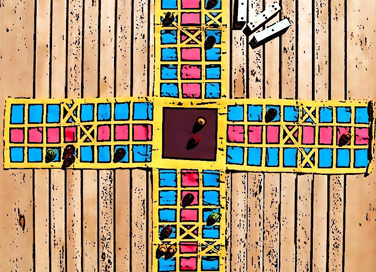

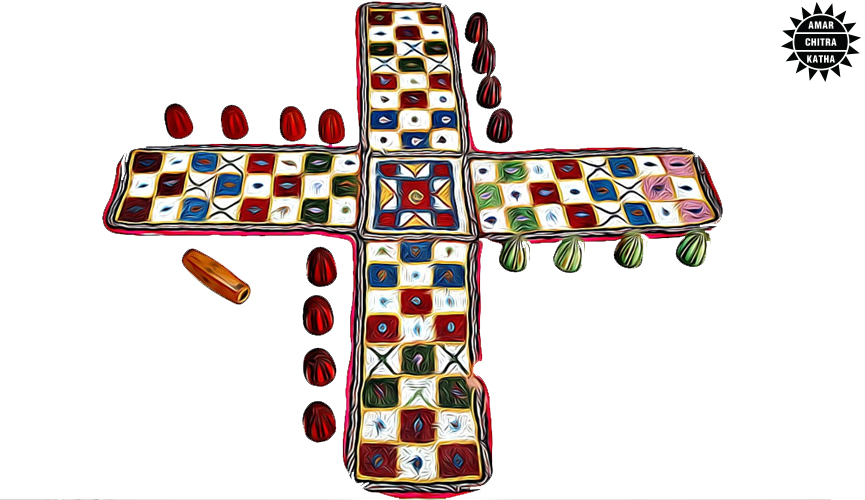

Believed to be the predecessor of the modern-day board game Ludo, Pachisi, was a cross and circle board game popularly found in ancient Indian texts. The game was played on a board shaped like a cross. Each player would throw six or seven cowrie shells (used as dice) and move pieces on the board until someone got all their pieces in the finish zone. The word Pachisi is believed to have been derived from ‘Pacchis’ meaning ‘twenty-five’ i.e. the largest score that could be thrown with cowrie shells. This game was so well-loved that emperors like Akbar would routinely play life-sized versions of the game, dividing the court itself into a large Pachisi board, with palace staff taking the place of the coloured pieces.

To receive more such stories in your Inbox & WhatsApp, Please share your Email and Mobile number.

Also called Mokshapat, Moksha Patamu, was an ancient Indian game that is believed to have been invented by Swami Gyandev in the 13th century AD. However, certain sources also suggest that it existed long before that time and was played as early as the 2nd century BCE. This game, which became the blueprint for the modern-day game of Snakes and Ladders, was originally intended as a moral lesson for children, along with being a mode of entertainment.

In this game, players would encounter ladders on the squares representing good deeds and virtues, which would take them closer to 100, which symbolised ‘moksha’ or salvation – the objective of the game. However, the squares representing bad deeds or vices would be marked by snakes that would take players to lower levels. To emphasise the difficulty one faces in attaining salvation, Moksha Patamu would contain more snakes than ladders – a rule that, along with the moral symbolism of the game, was lost when the game was popularised as Snakes and Ladders in colonial times.

Chaturanga, or Catur, was an ancient Indian strategy game that evolved into the modern-day game of chess. Named after the ‘chaturanga’ or ‘four-limbs’ of the army i.e. infantry, cavalry, elephantry and chariotry, this game has its origins in the Gupta Empire, with references dating to the 6th century CE. However, many historians opine that the game existed, albeit in varying forms, far before that period. Like the modern-day version, Chaturanga was also played on an uncheckered eight-by-eight board with moving pieces representing various parts of an army, with the objective being to checkmate the opponent’s King.

Also called Ashta Chamma, Chowka Bhara was a two or four-player game that was played in ancient India to hone the mathematical skill of young children. The game was normally played on a five-by-five board, with players throwing four cowrie shells to determine how many moves their pieces would make. The objective of the game was to strategically ensure that all of a player’s pieces or pawns are taken to the centre square. One of the oldest board games of India, Chowka Bhara has been mentioned in Indian epics like the Mahabharata. It also appears to be one of the most complex games – involving elements of strategy as well as chance. While there is no modern equivalent of this game, it is still played in certain parts of India today.

To receive more such stories in your Inbox & WhatsApp, Please share your Email and Mobile number.

Comic of The Month

The Sons of Rama

The story of Rama and Sita was first set down by the sage Valmiki in his epic poem 'Ramayana.' Rama was the eldest son of Dasharatha, the king of Ayodhya, who had three wives - Kaushalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra. Rama was the son of Kaushalya, Bharata of Kaikeyi and Laxmana and Shatrughna of Sumitra. The four princes grew up to be brave and valiant. Rama won the hand of Sita, the daughter of King Janaka. Dasharatha wanted to crown Rama as the king but Kaikeyi objected. Using boons granted to her by Dasharatha earlier, she had Rama banished to the forest. Sita and Laxmana decided to follow Rama. While in the forest, a Rakshasi, Shoorpanakha, accosted Laxmana but had her nose cut off by him. In revenge, her brother Ravana, king of Lanka, carried Sita away. Rama and Laxmana set out to look for her and with the help of an army of monkeys, defeated Ravana. On returning Ayodhya after fourteen years of exile, Rama banished Sita because of the suspicions of his subjects. In the ashrama of sage Valmiki, she gave birth to her twin sons, Luv and Kush.